WE ARE NEARING the five-year anniversary of the fire at Brazil’s Museu Nacional that devoured nearly twenty million artifacts. By now, we know the immediate and semi-immediate causes of this anthropological, archaeological, and artistic catastrophe, from the inappropriately installed wiring that led to the short-circuiting of an air conditioner, to the lack of sprinklers, to the systematic neglect (under the banner of austerity) of Brazil’s cultural institutions, to the global warming that necessitated the installation of the air conditioner to begin with. Among the treasures lost in the fire was a collection of objects that had laid the groundwork, forty years prior, for another museum’s exhibition. Conceived by the Brazilian critic Mário Pedrosa and the artist Lygia Pape, that show, “Alegria de viver, alegria de criar” (Joy of Living, Joy of Creating), was to feature the art of Indigenous Brazilians and, according to Pedrosa, was meant as a form of “historical, moral, political, and cultural reparation.” Pedrosa and Pape had designed the exhibition for the Museu de Arte Moderna, located, like the Museu Nacional, in Rio de Janeiro. In its first decade, MAM Rio had championed the Neo-Concrete movement to which Pape belonged and on whose behalf Pedrosa advocated; distancing themselves from what they saw as the extreme rationalism of Concrete art, the Neo-Concrete artists aimed, as they wrote in their 1959 manifesto, to embrace the “expressive potential” of art. For Pape (who, like a number of Neo-Concrete artists, had also belonged to the predecessor movement) and Pedrosa, this potential was exemplified by the objects they planned to showcase. As Pape said in an interview, the works by Indigenous artists had been created “with joy.” But “Alegria de viver, alegria de criar” never happened. The summer before it was to open, MAM Rio went up in flames and almost all of its collection was destroyed. This repetition of tragedy—1978, 2018—is uncanny, and it suggests that the tragic has a pattern. What seems strange and distant becomes familiar and urgent for the present.

The Neo-Concrete movement was famously short-lived, essentially moribund within a couple of years of the manifesto’s publication. When a US-backed coup deposed Brazil’s leftist president in 1964 and installed a military dictatorship that lasted twenty-one years, Lygia Clark, Ferreira Gullar, and other artists central to the movement fled. Pape remained. Among her peers, Pape always stood out for being left behind. During the Neo-Concrete years, she devoted herself to a seemingly passé medium with which she’d been engaged since the early 1950s: the woodblock. Newspapers singled her out, often simply calling her the gravadora, or printmaker. Pape would later theorize these works as the basis for her whole oeuvre, which came to span film, installation, and participatory performance. As the art historian Adele Nelson explains in her book Forming Abstraction: Art and Institutions in Postwar Brazil (2022), Pape “conceived printmaking as a conceptual foundation for her artistic practice. . . . She refused to view her early prints as mere preludes to participatory works of art” and instead proposed that “prints—that is, stationary works of art—can activate an experiential, phenomenological experience for the viewer.”

Much less studied than her later output, Pape’s woodblock prints of the ’50s, which she retroactively called “Tecelares” (Weavings), are finally the subject of an expansive exhibition. Curated by Mark Pascale and on view through June 5 at the Art Institute of Chicago, it features nearly one hundred works, many of which were damaged and have been painstakingly restored by a team headed by María Cristina Rivera Ramos. Still, as fragile works on paper, they show signs of age that announce their artifactual status and solicit historicization. They were produced contemporaneously with Brazilian president Juscelino Kubitschek’s ambitious plan for rapid industrialization (“fifty years of progress in five”), a massive endeavor that included the construction from scratch of a new capital city, Brasília. Oscar Niemeyer’s curvaceous reinforced-concrete buildings are the signal monuments of late-modernist utopianism, and for that very reason, Brasília’s structures—emblems of a national modernization project fueled by intensified slash-and-burn deforestation in the nearby Amazon—have also acquired a darker significance as cenotaphs for the entire project of modernity, which, after all, has brought us to this era, in which everything seems to be going up in smoke. Pape’s woodblocks index, foreshadow, and attempt to forestall the crisis of fire in which we now find ourselves engulfed.

In contrast to the industrial assembly line’s mechanical reproduction and the media’s mass consumerism, Pape usually made only monoprints off of her woodblocks. She would later say these works were, in fact, “paintings and not prints.” By embracing the monoprint and its inversion of the traditional reproductive utility of the medium, Pape emphasized each work’s singularity. She allowed the grain—the unique pattern of each block—to become a central part of the prints’ compositions, taking advantage of the fact that the lighter-colored wood that grows between the darker grains is more porous and can be scraped away relatively easily, emphasizing the undulating striations even more. The resulting prints imply a creative process that is reactive to the natural design of materials. Pape’s task became, not to employ wood for instrumental purposes, but to augment its intrinsic design—the artist as curator as much as maker.

Pape was not the first to foreground wood grain in her prints. In Japan, ukiyo-e artists had used the organic textures of their material to represent other natural phenomena, like the placid ripple of water across the surface of a pond. Pape was inspired by Japanese culture; she praised the compact form of the haiku, and she printed her woodblocks on Japanese paper that better registered the delicacy of the images. But rather than incorporating the lines of the grain into representational compositions, she treated them as a natural vocabulary of abstraction. Pape had turned her attention to the nonhuman rationality of the forest itself.

Wood grain visually records the metabolism of the tree from which a slab was carved. When water and nutrients are plentiful and the day is long, the tree grows quickly. Its growth slows in winter, producing denser, harder wood—the darker ring recognized as the wood’s grain itself. The seasonality of this cycle informs the casual rule that each ring in a tree represents a year of life, although environmental stress or unseasonal weather can leave a misleading record. Pape seems to have preferred quartersawn boards for her prints—that is, planks cut at a radial angle from the center of a tree, leaving the grain running in long, straight ribbons. The parallel lines, equally spaced if a tree grew the same amount each year, would be at home on a Concrete canvas. (The compositions of a couple of her prints from 1956–57 are eerily similar to Frank Stella’s “Black Paintings” of 1958–60.) But the point is that this was not a geometry calculated in advance by the artist. It was discovered, not invented; the artist’s task was not conception but manipulation.

And yet Pape did carve out her own geometry, too: thin, sharp lines straighter than wood grain ever could be; quadrilaterals with crisp right angles; polygons that tesselate, nestling snugly within one another. As Nelson writes, Pape’s woodblocks “juxtapose the precision of a blade-cut edge with the irregularity of wood’s natural grain.” On display at the Art Institute is a work from her “Ttéia” series, conceived in 1979 and revisited in the late ’90s, for which she installed golden nylon thread in arrangements suggesting the outlines of cylinders traversing a corner of a room: empyrean volumes filled only with light and air. Here, architecture is the preexisting element to be worked with and against. The prints could be read as an allegory of the literal containment of nature, of the desire for its disorder to be brought under machinic control, or conversely as a performance of submission to nature, a willingness to be directed by its rhythms, to become harmonized with the seasons. When we hold at the same time these competing interpretations, we may be tempted by a meta-interpretation that says we have already gone astray in our understanding by distinguishing humanity and nature to begin with. But Pape was ultimately a dualist, and this way of looking at the world was a key factor in her unique entanglement of gender and Indigeneity, labor and the environment.

IT IS COMMONPLACE to say of our age of anthropogenic environmental collapse that our folk dichotomies for parsing the world have collapsed too. What holds in the distinction between humankind and nature when isotopes from the fallout of Hiroshima mark a unique layer in the geological record beneath our feet? How can we claim a monopoly on subjecthood, on being the intentional agents in the world, when knowledge about the communications networks linking trees and fungi has filtered from peer-reviewed journals into popular documentaries? And how do we gain perspective on the world, locate a position from which to judge and intervene in it, when floods, droughts, and fires mean that the weather is no longer the backdrop to human drama but rather at the foreground of our anxieties? When dichotomies are no longer tenable, monism appears as both truth and cure: the truth that man and nature are inseparably one, and the cure that further disaster could be forestalled if only we became one with nature once more.

But this flattening of nature and society, planet and human, in fact has very few philosophical or practical merits to recommend it. It is, after all, human action that is needed to put our pollution addiction into recovery and reduce carbon emissions—which is why this counterproductive monism is the central object of critique in Kohei Saito’s recently published Marx in the Anthropocene, an English-language book that builds on his 2021 Asia Book Award–winning Hitoshinsei no Shihonron (Capital in the Anthropocene). For Saito, an analytic distinction between nature and society is a prerequisite for appreciating and adjusting society’s role in nature and vice versa, and in his view, it was Marx’s great discovery that what manages this duality is labor, which is defined in the first volume of Capital as “a process between man and nature, a process by which man, through his own actions, mediates, regulates, and controls the metabolism between himself and nature.” Marx remains indispensable for navigating our age of climate change, Saito argues, because he understood ecological crisis as a “metabolic rift”: an asynchrony between the timescales of capital and those of nature. Capital always wants its goods faster than natural cycles allow, whether we’re talking about the creation of fossil fuels over the course of eons or the replenishment of soil nutrients over the span of just a few years.

Pape’s monoprints—singular yet not heroically original in the manner of artworks that have no template, combining the kind of organic patterns coded as feminine with a straightedge rationality typically associated with the masculine—might at first seem to collapse dualities in the way Saito critiques. Such a hybrid agency may also be seen in a work on view in the Art Institute show, her 1958 Ballet neoconcreto I, choreographed concurrently with her production of woodblock prints. In this performance, dancers move opaque cylinders and rectangular prisms like chess pieces, providing an abstraction both of body and of machine, testing the limits and affordances of their interface: both prosthetic enablement and rigid confinement. (Three years later, Robert Morris thought of putting himself in a remarkably similar rectangular prism onstage and falling down, but he ended up relying on a stage device in the performance of Column, 1961, providing a different intimacy with geometry as a proxy body.) Her monoprints, in a manner of speaking, choreograph similar kinds of testing and tension. But rather than flattening ecology and technology, they consistently emphasize Pape’s own hand in directing the materials of nature, even as she departs from a superrational drive toward mastery over nature for mastery’s sake. This is true throughout her evolution in the 1950s. One of her first prints, from 1952, shows seven asymmetrical boomerang shapes variously rotated without any apparent systematicity. The seven shapes are similar but, on careful inspection, not identical. Forensic analysis by Art Institute conservators has revealed that a single piece of wood was used for all seven impressions, but Pape employed a stencil to expose different parts of the template, creating variations in the shape.

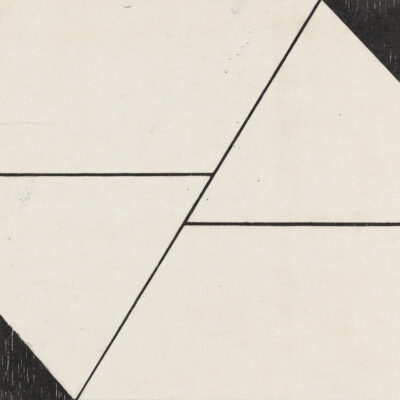

Pape sustained this iterative, modular approach in later prints, but the process shifted in important ways. In a number of prints beginning in 1955, she experimented with a small triangular block that she used to build larger triangles—not simply pyramidal magnifications of the basic unit, but lattices of positive and negative space. The grain runs parallel to one side of the block so that the triangle is effectively composed of a stack of progressively shortened lines with the longest at the base. These lines run parallel to the longer edges of the rectangular paper. Pape meticulously planned the placement of the modules, and traces of her graphite guidelines remain visible. More strongly than in the earlier work with seven rotating forms, she constructs a grid, aligning and intersecting natural and man-made geometries.

But the spatial confluence within a single composition of aleatory ecological processes and mathematical calculation betrays a temporal dissonance. A tree’s metabolism yields only one line a year, whereas Pape can draw one in a minute. Wood grain is the crystallization of history into an image, often at scales much larger than a human lifetime. Pape’s woodblock prints stage the incommensurability of these temporal registers. They show an aspiration to grapple with material and to make it speak the language of formula, and they show that this must always remain an aspiration: a desire impossible to consummate. They show the limits of Concrete preconception, because the mind must always run up against a world, a planet, whose materiality cannot be synchronized by an idea. And they show, in turn, the limits of monism as a fantasy of ecological repair, for it turns out metabolic rift cannot be healed. As a chronic condition, it can only be managed.

MOST OF THE NEO-CONCRETE ARTISTS supported the conservative National Democratic Union party and were invested in newspaper art criticism aimed at constructing a bourgeois middle class through the cultivation of artistic sensibilities. (The Neo-Concrete manifesto was published in Rio’s Jornal do Brasil, whose circulation was nearly sixty thousand, dwarfing that of European avant-garde magazines from earlier in the century, such as De Stijl, which had a circulation of just a couple hundred.) Still, the movement has tended to be read as a kind of fellow traveler within the lineage of committed left avant-gardes in the Constructivist mold. While, on the one hand, Neo-Concretes advocated for art’s autonomy as opposed to an embrace of art’s instrumentalization in the service of radical politics, on the other, they saw capitalism as an antagonist that transformed producers into machine cogs and consumers into conformists; to counter these depredations, they sought a revitalization of human experience. Assessing the contradictions of this political orientation, Mariola V. Alvarez writes in her monograph The Affinity of Neoconcretism (2023) that “the [Neo-Concretes] in their quest to produce objects for private experiences did not recognize the role they played in consolidating the relationship between modernism and the bourgeois subject.” And perhaps this tension is one reason the official Neo-Concrete movement did not last long into the 1960s, which saw what art historian Sérgio B. Martins, in Constructing an Avant-Garde: Art in Brazil, 1949–1979, calls its leading author Ferreira Gullar’s “defection from neoconcretism and subsequent embrace of the didactic aesthetics of the student movement, with its emulation of popular and folkloric art forms and its underlying Marxist orientation.”

In her participatory works of the 1960s and ’70s, Pape, too, would engage the politics of class through an aesthetics that was, if not didactic, at least emphatic. She undertook a research agenda that especially explored the racialization of class: in the favelas where the populations recruited for constructing Brazil’s modernity found themselves remaindered by it, and in Indigenous communities, which, as her and Pedrosa’s plans for “Alegria de viver, alegria de criar” unwittingly documented, were globally exoticized in a romantic vision that obscured the land and labor stolen from them. Pape’s later visits with Indigenous cultures throughout Latin America allowed her to critique this romanticization, as in Our Parents “Fossilis,” 1974, a short film that displays postcards tourists would typically buy depicting Indigenous people as barbarous beauties. But labor was already a central concern of Pape’s printmaking in the 1950s. As Nelson writes in the catalogue for the Art Institute exhibition, Pape curated her image in photographs that “foreground[ed] her labor, not her face, centering her fingers pressed against her work or her body hunched over a collage on the floor in her studio.” Tecelares was a Pape coinage; as Nelson explained in a 2012 Art Journal essay, this terminology “expanded the field of references for the interpretation of her work beyond the fine arts to include culture as a whole and specifically traditional and indigenous cultures.” We might add one more reference: Early in 1953, shortly after Pape began developing her first woodblock prints, São Paulo witnessed the famous, nearly monthlong “strike of the 300,000,” primarily led by textile workers, who were mostly women.

Writing in 1957, Pedrosa said Concretist painters wanted to “get rid of all direct phenomenological experience” in order “to realize a pure and perfect mental operation, like the calculation of an engineer.” Like the “planned city” of Brasília (which was then under construction), Concrete art posits that there is both a plan and a material product that is the realization of that plan. What falls out of frame is the labor that connects plan and product, like the workers’ hands that had to manually smooth the curves of Niemeyer’s buildings. As the art historian Aleca Le Blanc has written, “Despite the modernized appearances and the industrial ethos that was pervasive at the time in Brazil, these buildings were more like handmade sculptures than products of a truly developed nation.” Whereas this labor is obscured by the fetish both for the genius of the artist and for the spectacle of the monument, Pape’s woodblock prints make visible the labor of making itself.

Moreover, they make visible a form of labor sometimes effaced by Marxist accounts themselves, a labor referenced both by the “women’s work” invoked by calling these prints “weavings” and by the traditionally reproductive capabilities of the woodblock medium itself—that is, not the productive labor that makes commodities, but the reproductive labor that births, raises, cares for the people who make the commodities. Like many Brazilian women artists of her generation, Pape would likely not have identified as a feminist; in interviews toward the end of her life, she rejected even the identity category “Latin American artist.” As Claudia Calirman notes in her 2023 book, Dissident Practices: Brazilian Women Artists, 1960s–2020s, women have for so long been central to the Brazilian avant-garde that “there was no ‘Brazilian’ equivalent to Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ because there was no need: the assumption was that female artists already ‘had a place at the table.’” But there is nonetheless something ecofeminist in Pape’s works, in their attention to all the labor that forms the background condition of Brazil’s modernization: the labor of the planet that grows trees; the labor of women who raise workers; the labor of racialized workers who realize an architect’s vision.

Metabolic rift cannot be healed—the timescales of nature and of capital are irreconcilable—but the final effect of Pape’s monoprints, in their simultaneous evocation and foreclosure of reproduction, is at least to synchronize a kind of ending: The tree that has been cut down to make the woodblock will make no more wood, and the woodblock that has produced the monoprint will print no more prints. Another term for the refusal to print, the refusal to do the labor taken for granted, belongs to the collective action of those São Paulo textile workers in 1953: the strike. To call these woodblocks “weavings”—with wood grain and blade-cutting as the warp and weft of Pape’s new textile—is to suggest the strike as the site where the duality of labor and nature come together in the face of capital’s voracious appetite to use up each and spit out both: coming together not in a monism of essence, but in a coalition of refusal.

Michael Dango teaches at Beloit College and is the author of Crisis Style: The Aesthetics of Repair (Stanford University Press, 2021) and the forthcoming 33 1⁄3 volume on Madonna’s Erotica (Bloomsbury, September 2023).